Hülya Atalay

■ visual artist. performer.

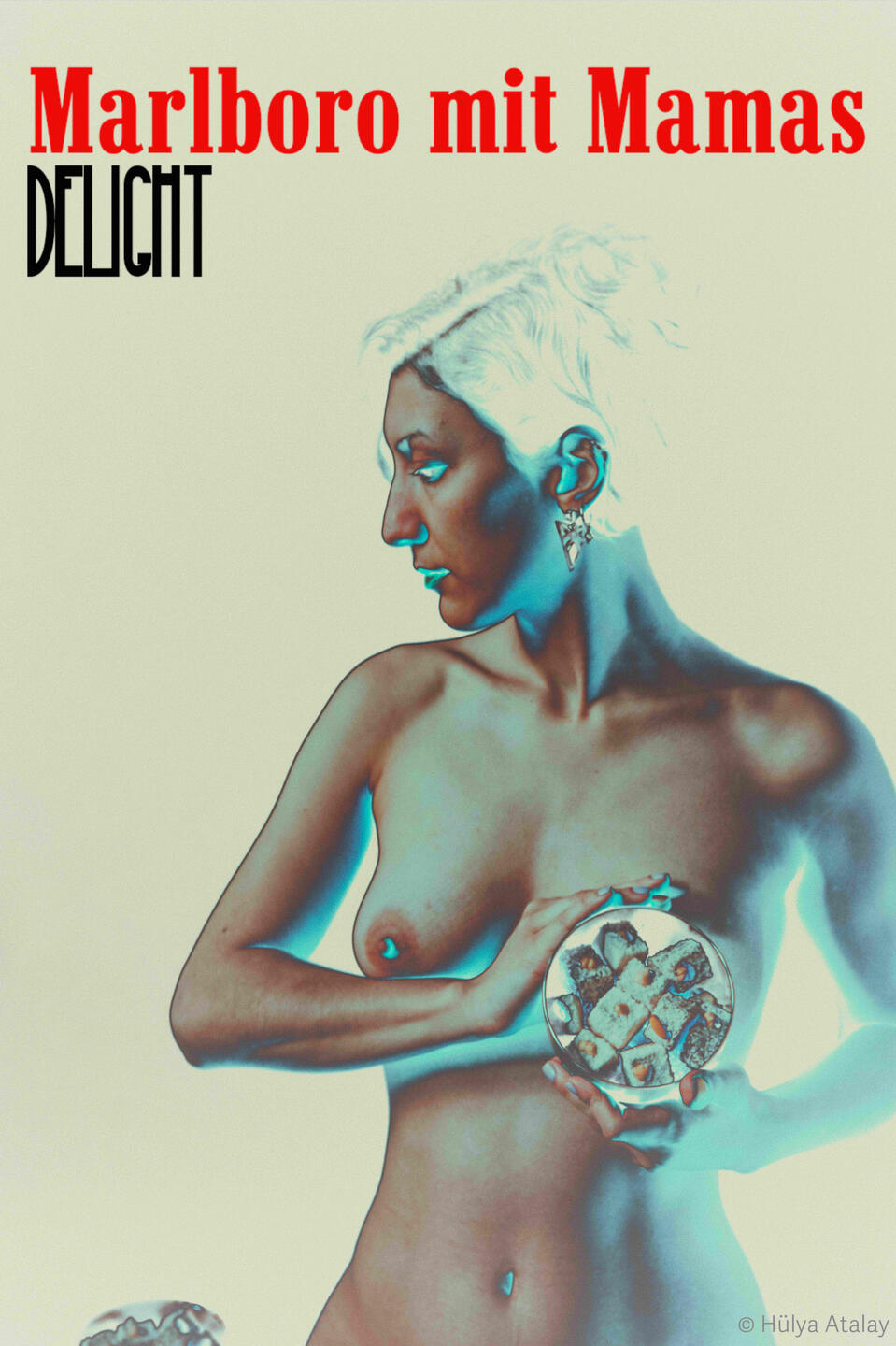

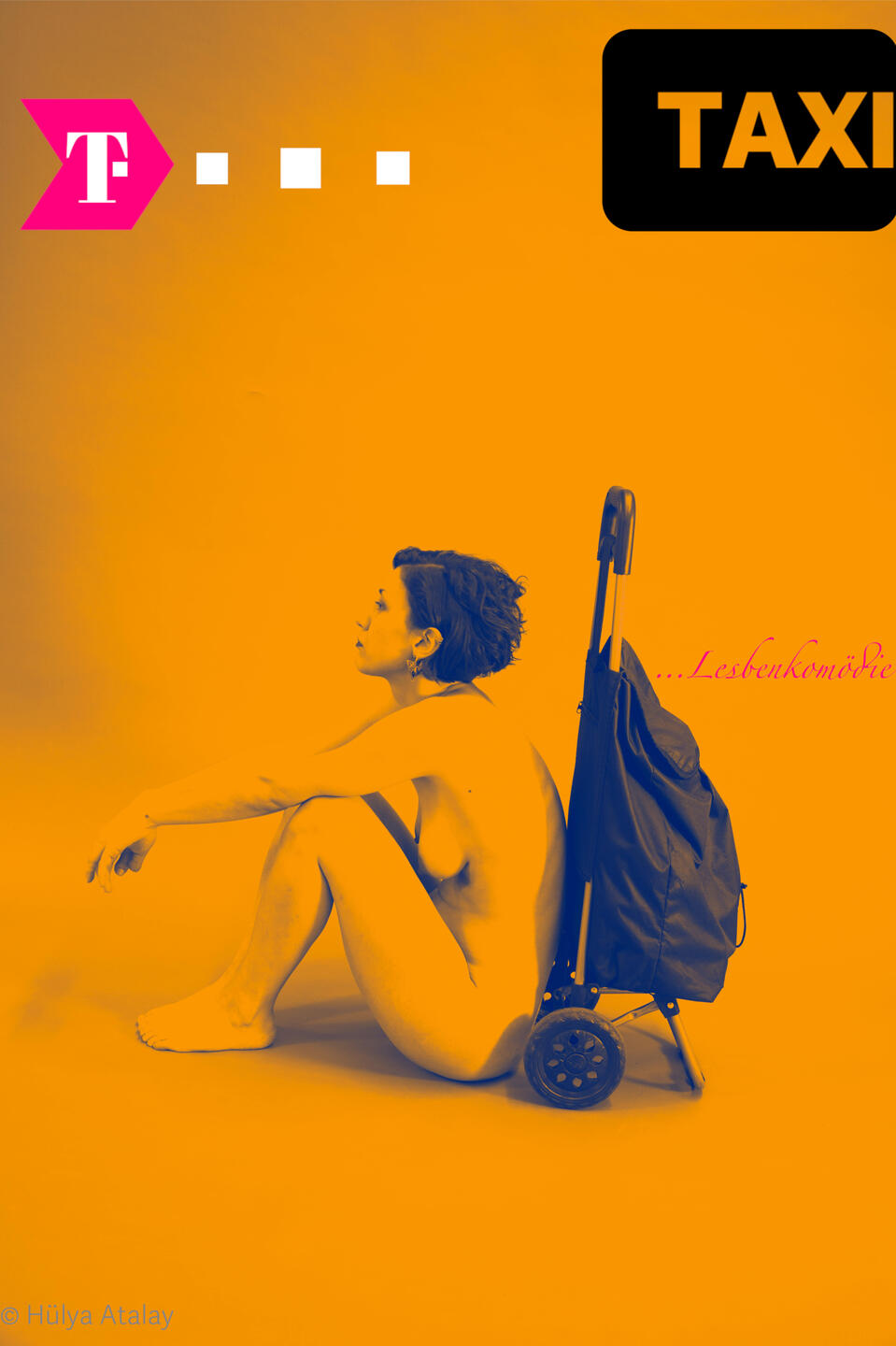

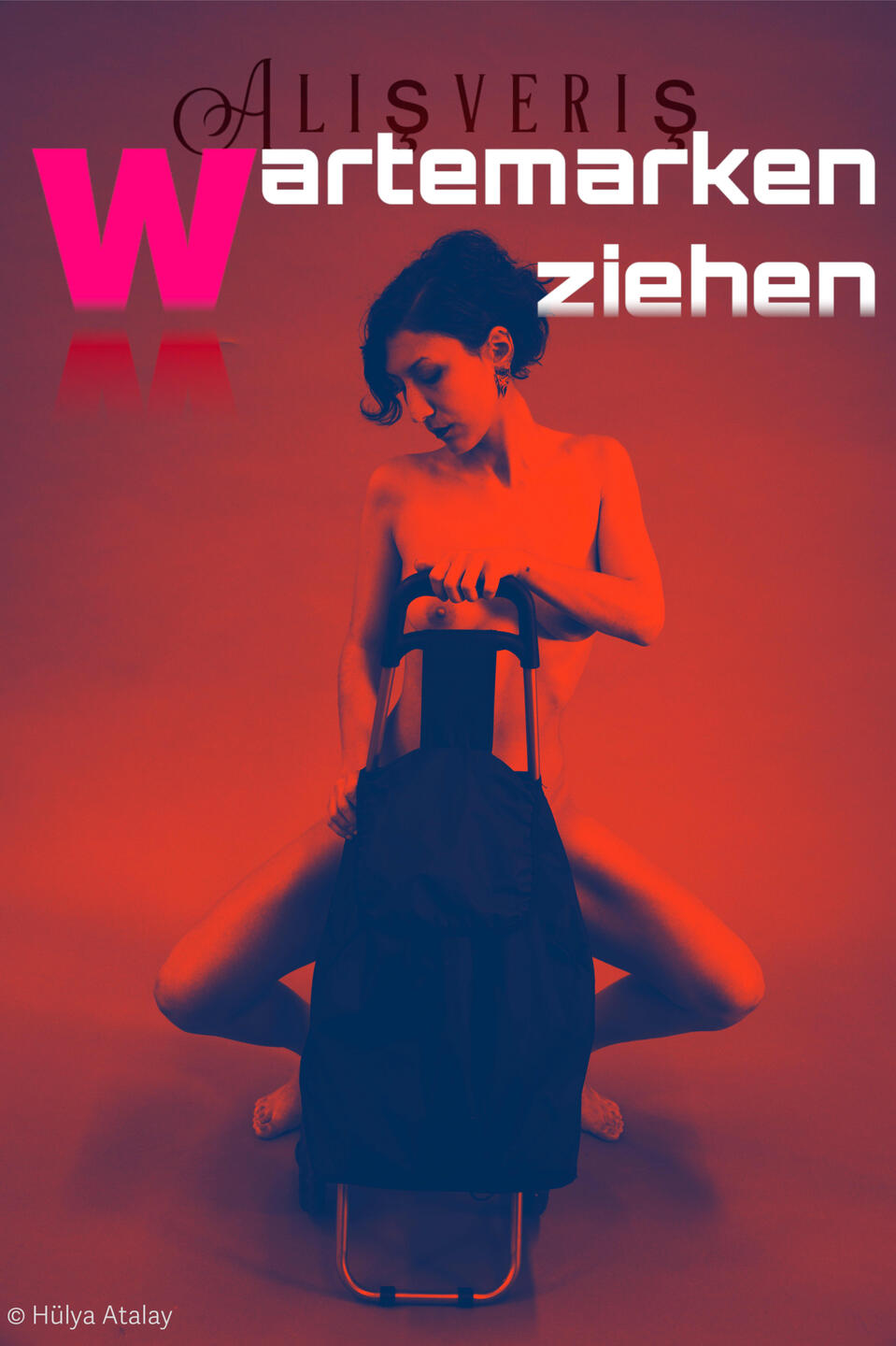

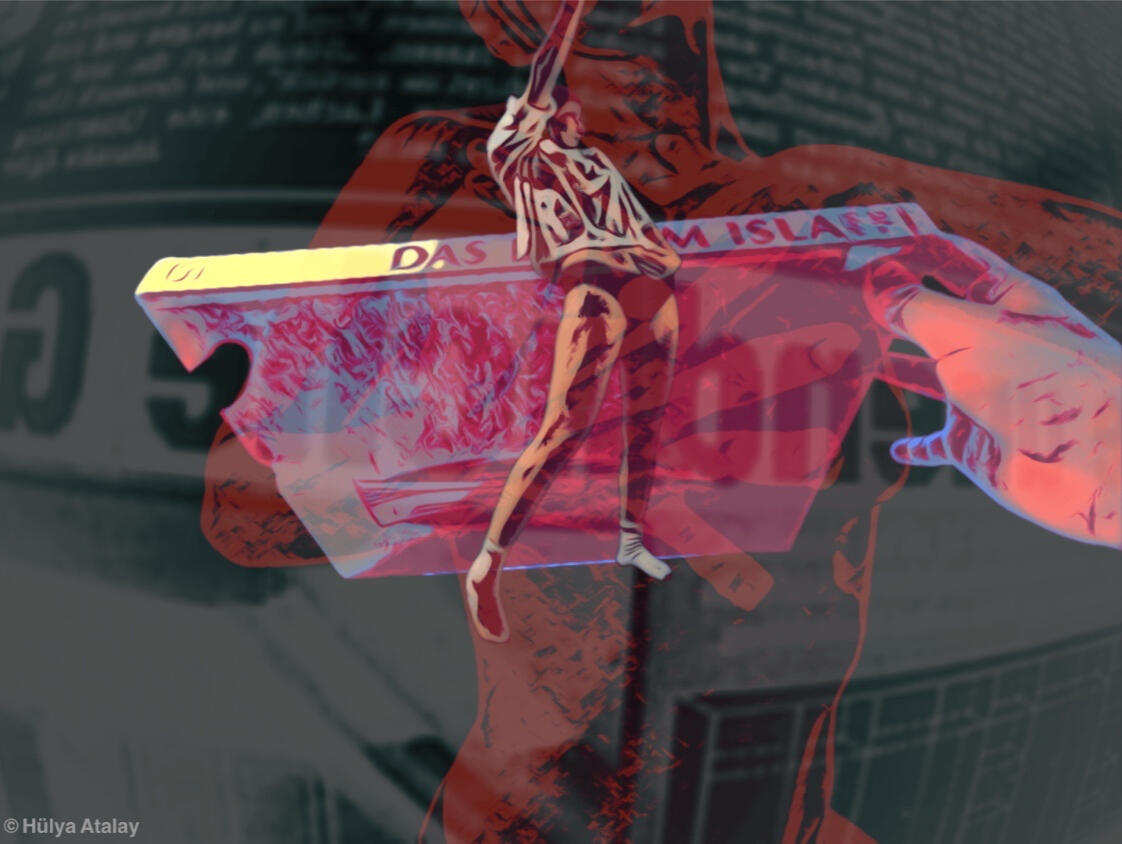

■ "Upcoming movie posters"(photographies. 2025.)

In this photographic series, film posters are shown for films that do not exist.Both in their typographic design and in the visual composition of film posters, references to temporal narratives are made. They function as a kind of trailer for films, creating a general dramaturgical atmosphere meant to evoke curiosity and anticipation for stories yet to be told.Typefaces, within the histories of writing, make references to times and places; yet in the dominant film industry, the choice of typography is typically self-referential. It continues to point back to the same places and the same stories, which are then classified under fixed “movie genres.”In this series, existing typefaces are used. However, the film titles are in German and/or Turkish and refer to people living in Germany with Turkish biographies. They explicitly highlight women* and lesbians of Turkish descent living in Germany.

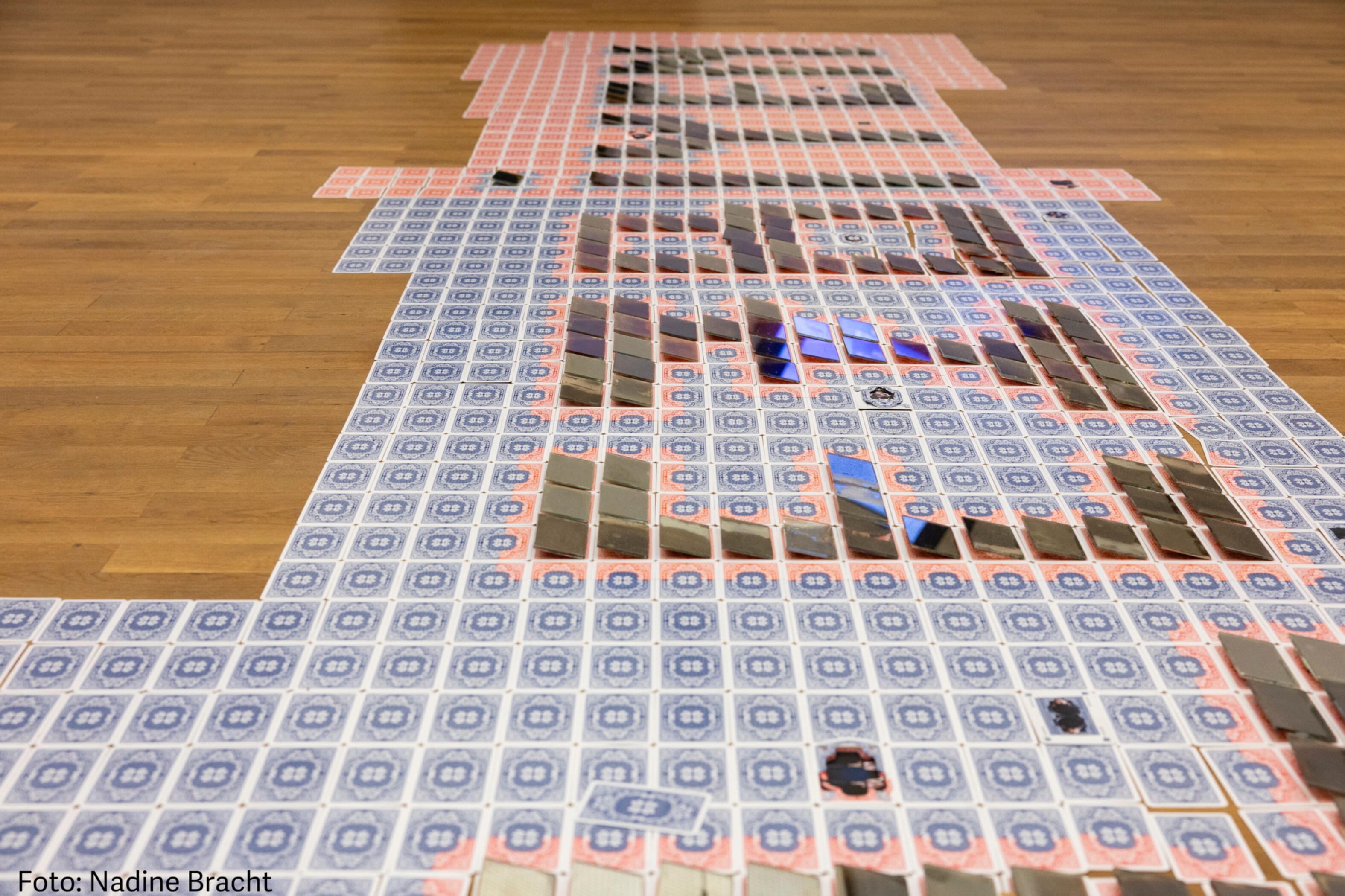

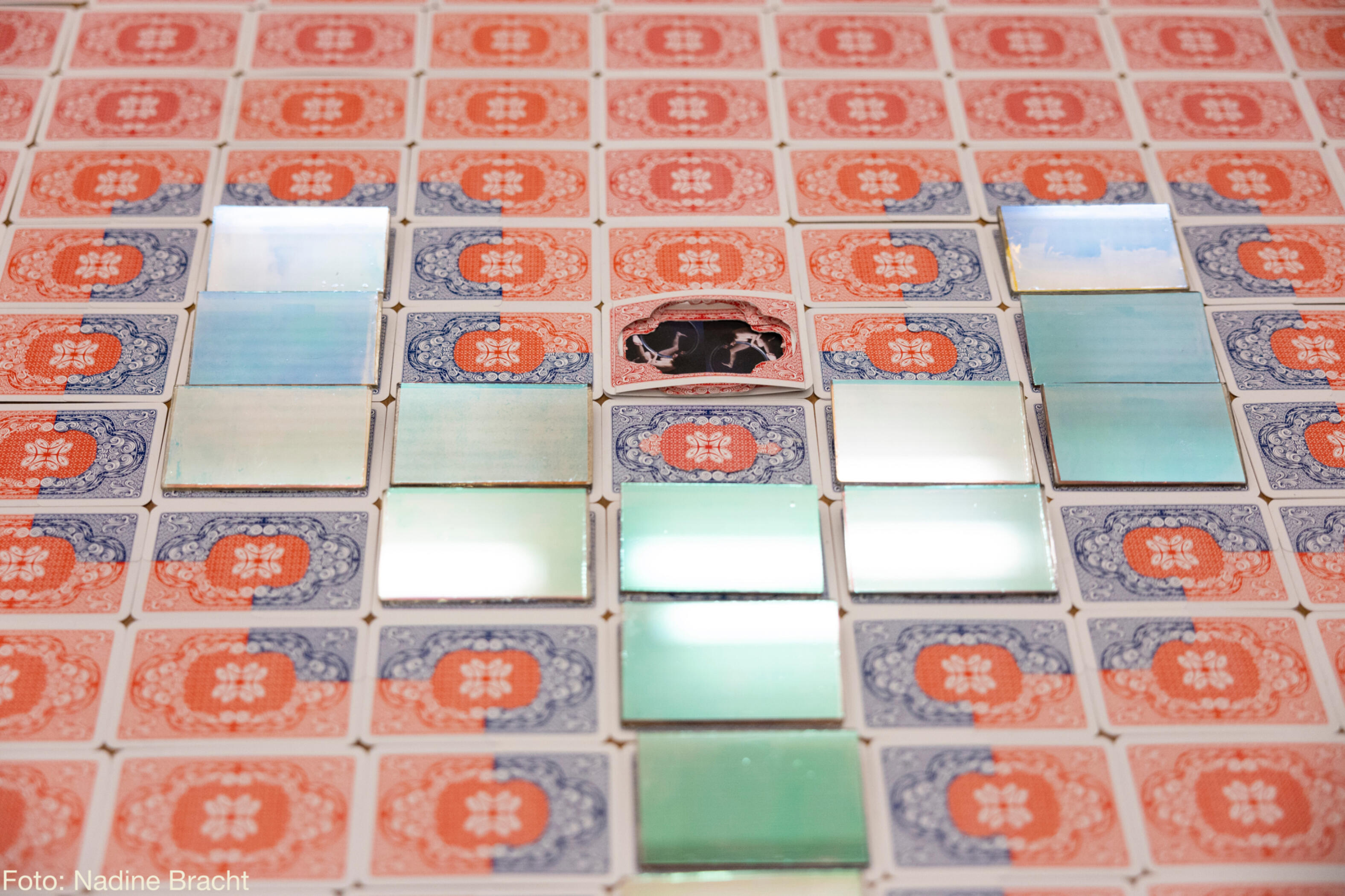

■ "Erotische Gesellschaftsspiele. Kulturelle Gedächtnisse sind mit ihren Outings überfordert."

(Installation. 2025.)

(group exhibition. 'A-Z. Mapping the Future.' 17. - 26.10.2025. Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart).

In this floor installation, I arrange commercially available playing cards—commonly found in grocery and household stores run by diasporic communities in Germany, specifically sourced from a Kurdish store—on the ground.They spell out the Turkish word for lesbian, Lezbiyen, on the floor.Playing cards are usually played on a table, a raised surface where the eyes can strategically scan and plan the game. Here, however, they lie on the floor—on floors, where I bake bread with my mother, my grandmother, my sisters, and my aunts. Between the cards, I place miniature photographs in which I relate my naked body to a baking tray, Tepsi.I continually ask myself who makes the rules, who is regulated, who plays, and who is played: and whether play is ever truly removed from the seriousness of life—or merely a miniature version of reality.In my family, gambling addiction among men has a long history. Playing cards are objects of value, substituting for a value that the men in our family do not possess—namely, money. Historically, playing cards have also been used for colonial and imperial propaganda purposes. In these games, which mirror a larger political system however, those who gain nothing at all are BIPoC women*.I wonder what happens to the meaning invested in playing cards when the lesbian experience is addressed from a Turkish-biographical perspective. The miniature photographs are not pin-ups; the cards cannot be played with—they are a fixed, immovable part of the installation. Women who articulate their own roles and sexuality in their own words remove themselves from normative attempts at categorization—and they tell their own stories.As a rule, these specific cards can be purchased in two versions, blue and red. I wondered why this is the case. In this installation, both colors lie on the floor, and Lezbiyen rises from them through small handcrafted mirrors, in which one can visually perceive oneself in a fragmented way. The history of playing cards is inseparably entangled with the territorial division imposed by cartographic standardization policies. What we are supposed to perceive as the “front” in a game appears as the European side of the cards. I have wondered since childhood why the back of the cards resembles the carpets we had at home.Consciously, I place the word Lezbiyen with this side facing up. When we play cards, we pretend to hide what carries meaning behind the so-called “back” of the cards. Yet every game ultimately has a rigidly defined ending, with winners and losers. To hide something in plain sight, while everyone knows it is there, is erotic.Eroticism, however, has a very particular significance among women who love women; it does not play by heteronormative, patriarchal rules. It represents the ultimate deviation from a reproductive notion of tenderness, in which a woman is expected to bear a man's legacy—both physically and psychologically. Women express tenderness toward one another differently. When it comes to sex, our intentions are not goal-oriented.One might also consider whether sex is a microcosm of broader systems.

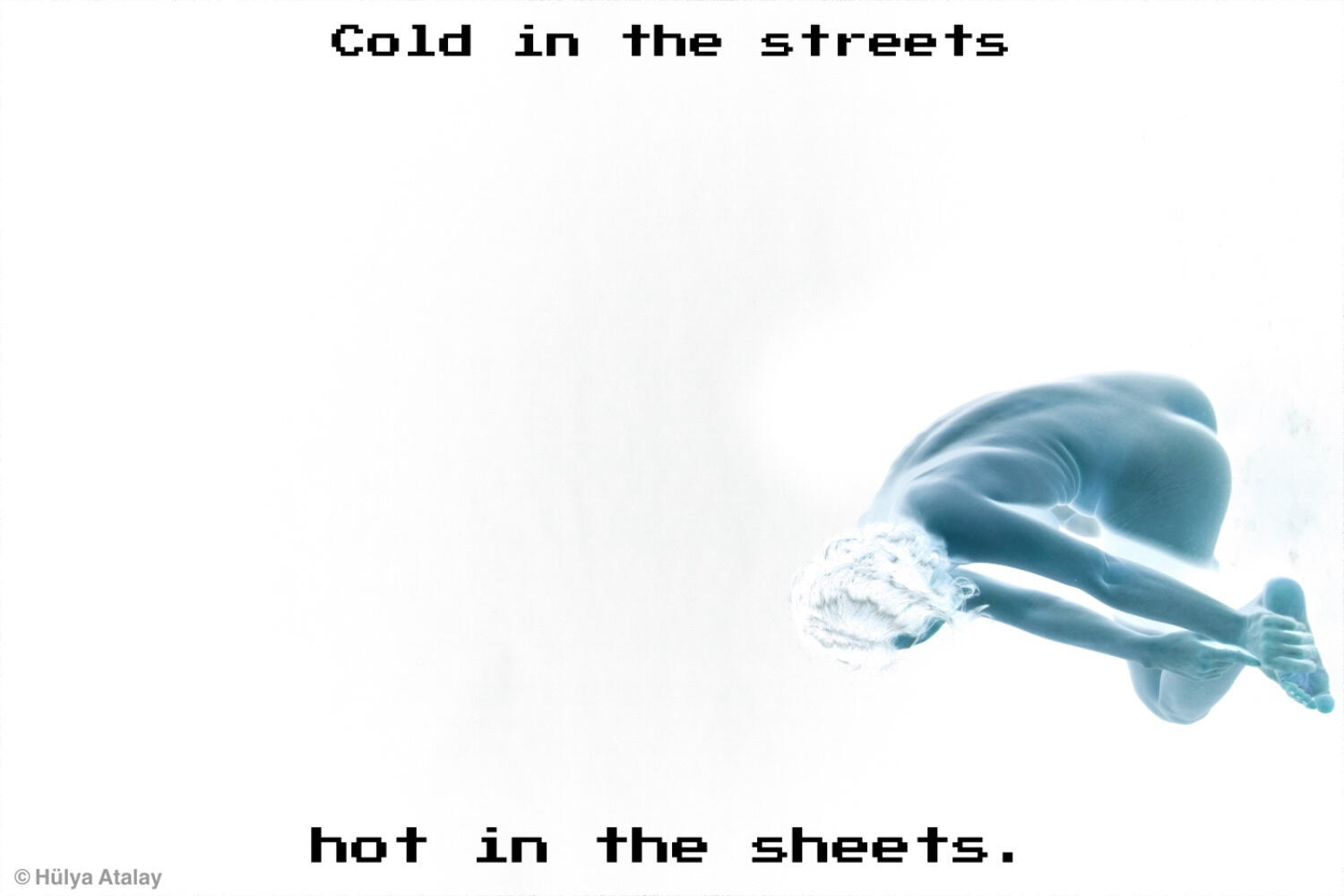

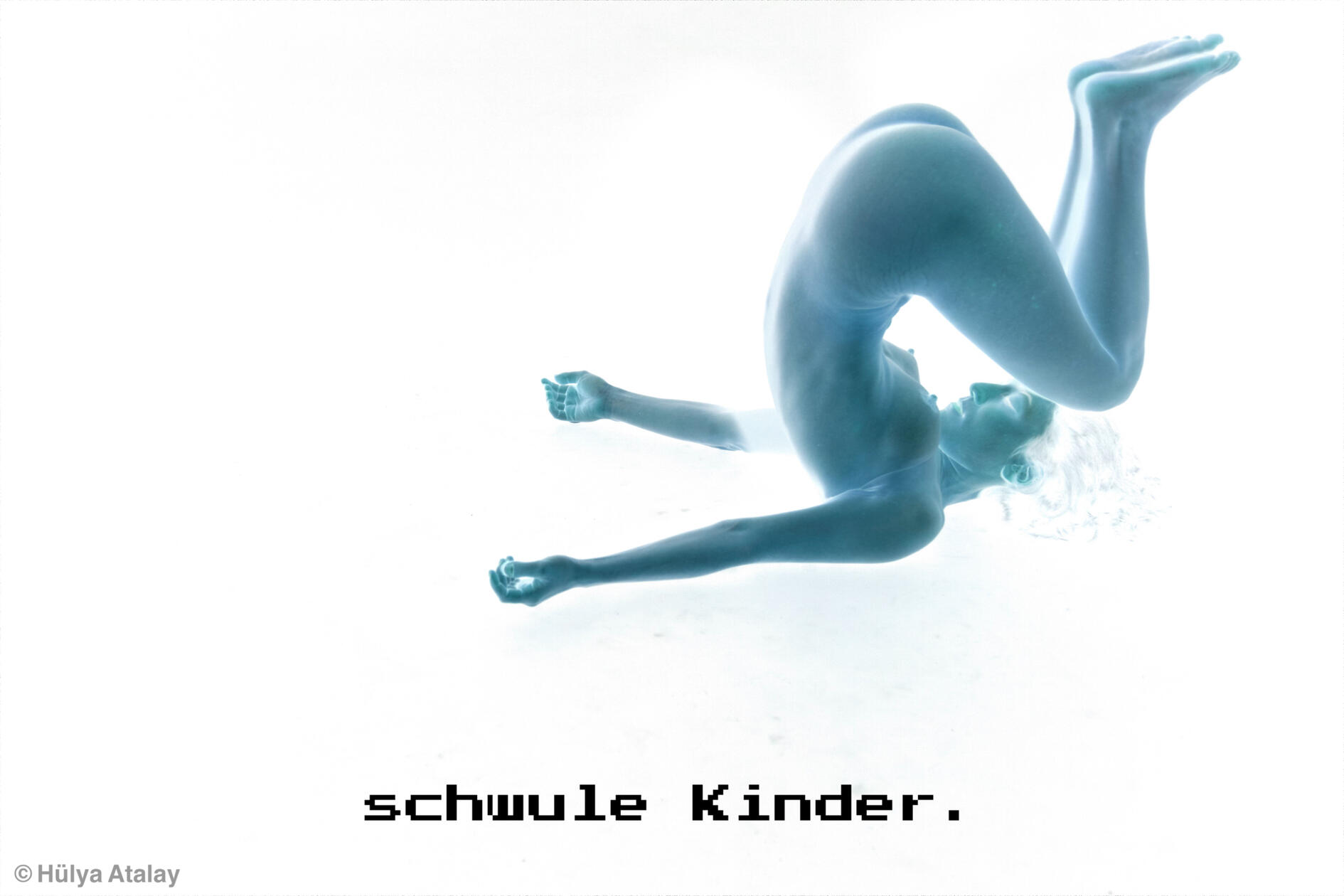

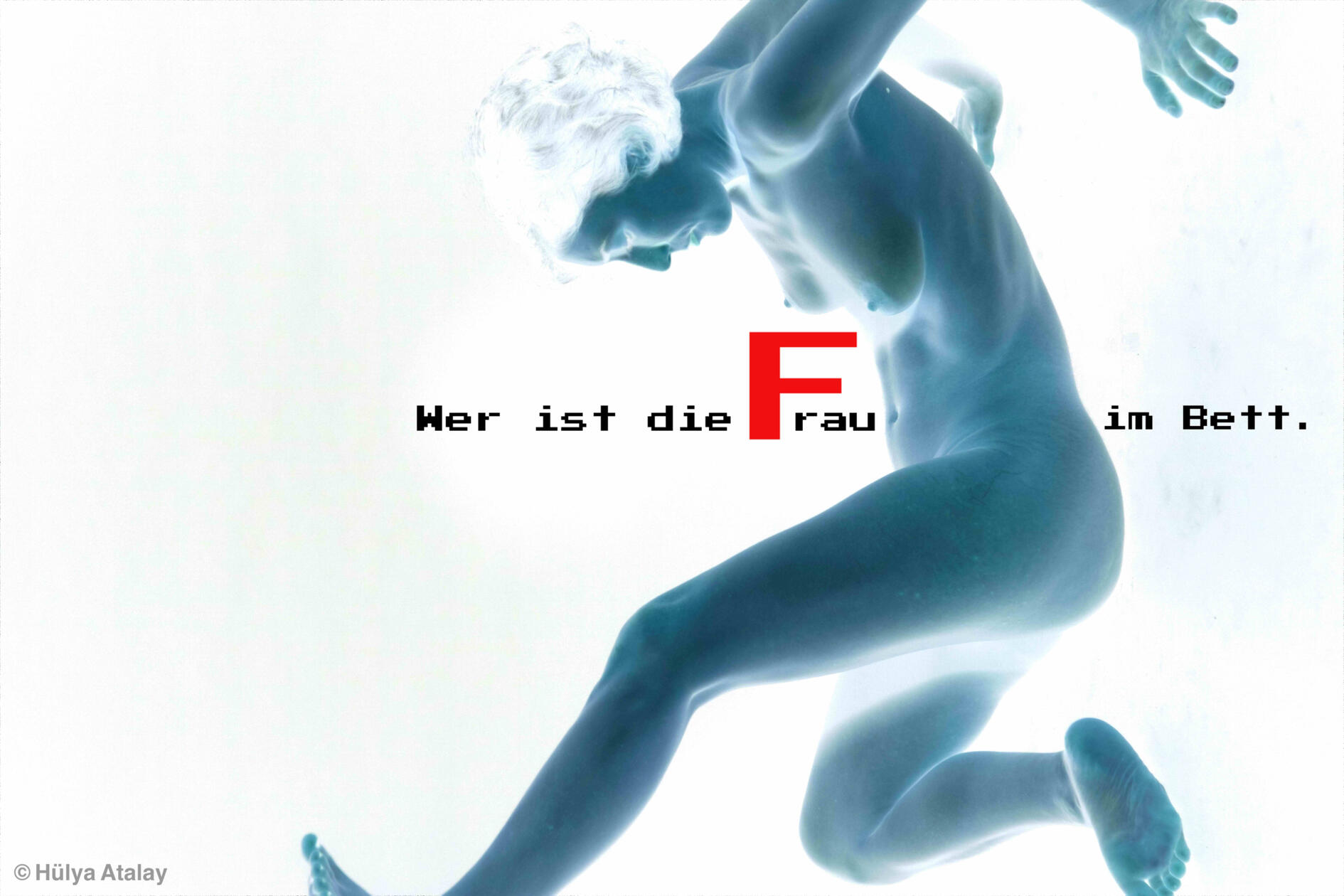

■ "L-Wort" _ (series)(photographies. 2025.)

Throughout the first episodes of the Showtime series The L Word (2004, USA), the main characters discuss the visible codes of lesbians.“Cold in the streets, hot in the sheets,” says one of the main characters, as the group of friends tries to figure out together whether one of their friends’ crushes might be a lesbian.In this selection of color-inverted photographs of my naked body, I add prejudices—expressed by (openly) heterosexual people—against homosexuals, based on my experiences in a German context. All center around the image of the “cold, distant” lesbian, who is essentially addressed as a “too complex, too critical” woman.Showtime was a premium cable network; you needed a paid subscription to watch the show in the 2000s. This meant that one had to pay in order to access women’s fantasies about lesbian relationships, friendships, and sex.Entering depictions of lesbians through this show—specifically in 2025 in Germany—still means that you need internet access and must pay subscription fees to channels similar to Showtime. Thus, the depiction of lesbians and their narratives—given the crucial role of visual and acoustic media in socializing our perceptions of romantic relationships—continues to have restricted access.

■ An open-process performance in the residency "crack:s" (in collaboration with WKV, White Noise and Fitz Figurentheater, Stuttgart)(Sound Performance. Group Showing. 03.-09. November 2025. FITZ Figurentheater, Stuttgart. 2025.)

During the week-long residency, sound samples of women singing in Turkish were layered and tested as a shared sonic space in combination with my own singing voice.

The rhythm is driven by a moan that is gradually pitched up to the point of exhaustion—a mechanical, repetitive, unsensual moaning, the unreal sound of the fictive notion of penetration and of heteronormative conceptions of sex.The voices of singers such as Neşe Karaböcek, Sertab Erener, Zeynep Bakşi Karatağ, Selda Bağcan, Ayben, and Tülay German were gradually superimposed to the extent that it became impossible to distinguish who was singing what; at times, the layering itself became the central focus. I gradually replace the voices with my own, removing sounds that had previously been present.Throughout the process, the red light shifts to ordinary bright stage and audience lighting. The moaning remains. It slowly fades away.

■ " studies on lo-fi studies "

(Video. 2025)

The category of "low fidelity" appears to lack details, in sounds as well as in images. However lo-fi is a nostalgia machine, providing those with very specific, time-based material who already have an abundance of resources to retell their own (hi)stories.For this video I put two songs into a dialogue, which already have been put into a dialogue before, yet in another form: Mos Def (Yassin Bey) released his song "Supermagic" in 2009. It uses a spoken-word-sample by Malcolm Xs' speech "Message to the Grass Roots" (1963) in the beginning as well as parts of Selda Bağcans song „İnce İnce Bir Kar Yağar" (1976), which gives the whole song its leading rhythmic patterns.

The Japanese anime Dragon Ball Z from the 1980s is part of Germany’s pop-cultural memory. It raises questions about why the German visual media landscape remains permeated by imperial and colonial narratives.I grew up in the early 2000s. Before smartphones, many diasporic parents were accused of 'parking' their children in front of the TV, of exposing them to too much violence.Now, as an adult, I wonder why others rarely reflect on how violence—often stylized or cartoonish—was normalized, appearing both on the packaging of childhood products and across the visual culture that shaped us.--- A wordplay referencing the family name Brandt—the brand behind German Zwieback (rusk) production.During World War II, Zwieback was considered a “war food” for Nazi soldiers due to its long shelf life. In the post-war years, it remained a staple in German households amid raw material shortages. The baked good thus became a childhood memory for a generation shaped by war and its aftermath—a nostalgic material.There are no statements on the official Brandt family website, nor in any other sources, regarding the forced laborers who, between 1939 and 1945, were compelled to produce Zwieback in large quantities in Hagen.The identifying feature of Brandt Zwieback packaging is a smiling, blonde child—a 1989 graphic continuing earlier versions since 1929, idealizing the notion of “the healthy child.”Zwieback is still recommended for digestive issues and thus carries additional meanings. In this photograph, I present the Zwieback package as a commercial product, held in front of the camera by a hand reminiscent of Apple product photography. The hairstyle remains blonde, but here it is borrowed from the anime protagonist Son Goku of Dragon Ball Z. He is also blonde—but only in his “advanced” form. In the anime’s narrative, Son Goku is depicted as half-human, half-ape—a racialized storyline.

Throughout the series, he disciplines his body until he transforms into a strong, blonde, emotionally detached man.Both the child on the Zwieback package and the anime hero articulate an ideal of the healthy, white man—a construct shaped by fictional narratives and performed through visual expressions of whiteness and masculinity.Zwieback is only bread. Yet imagery that idealizes white bodies continues to generate profit.

■ "Abwesende Stimmen in lebenden Körpern"(Video. 2025.)

The video opens with quotes arranged in a triangular movement across the screen. Praying gestures, adopted from cinematic conventions, appear — often interpreted as religious, specifically Christian, signs. The quotes build gradually, beginning with Adolf Loos’s patriarchal view on sex in 'Ornament und Verbrechen', which frames male penetration upon the cross as an “original” ornament.By repeating the white cross against a black screen, a mocking gesture is being built up gradually . Subtitles move with the images, integrating scripture into the visual flow and establishing a rhythm that carries into the movement of repetition. Repetition underlies both litany and the notion of "ornament". Historically, western academics described so-called “primitive” patterns as less valuable than christian, iconographic images, despite their own repetition — a concept applicable to liturgical speech.Building on repetition, the video introduces layered voices: a turkish reading voice paired with a german repeating voice. This opens an acoustic space previously silent, while the turkish text, from Elif Şafak’s Pinhan, retains its autonomy and gender-fluid perspective. As the german voice enters subtly, it forms a whispering texture. Repetition of terms such as “a repetition,” “an original,” “a copy” are mocking the embodiment of speech: language is often reproduced rather than internally generated, raising the question of whether we speak or are spoken by language itself.

Spontaneous photo taken in the subway. We talked. He didn't know why I was feeling uncomfortable,

sitting infront of his open legs in the public. I asked him, whether I could take a picture of us and turned my phone towards him, so he could see what I see. Than he excused himself, I wished him a nice rest of the day.I color-inverted the photograph later in the studio, highlighting the person holding the camera. And an umbrella.

■ "no title"(photography. 2025.)

■ "Strip, kein Tease."(Performance. Video. 2025.)

Some videos don’t need a description.